This month, I am highlighting commemorative works in DC that feature youth. The physical form of commemoration needs not be a statue, although many are. I'm looking to see if a young person is included as part of the commemorative narrative, or that a young person is central to the story of commemoration.

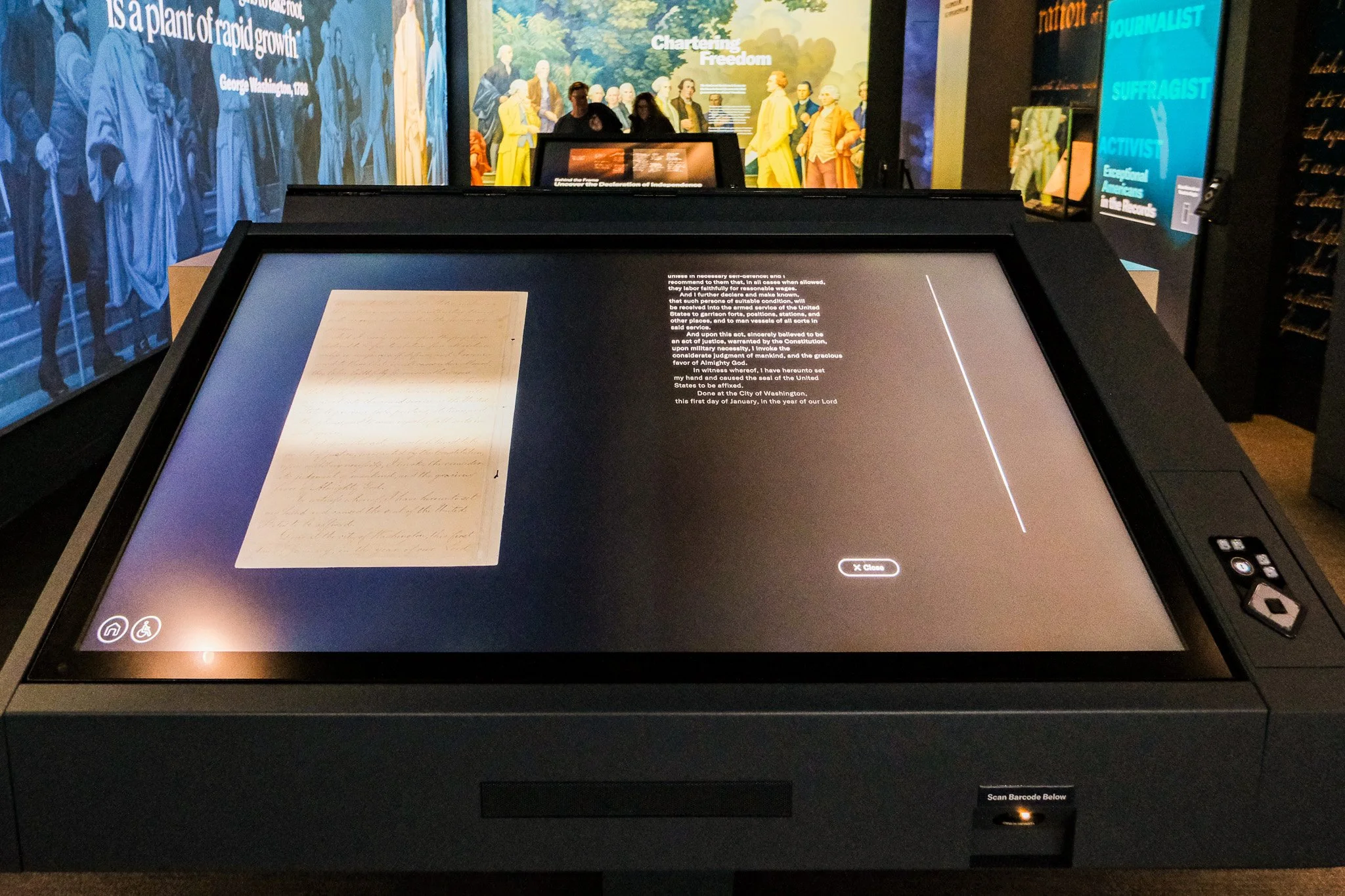

Old pump house converted into a learning center.

Let’s start next to the Anacostia River in Southeast DC, looking at a different type of commemoration. This place honors a young man and a young woman, both who served DC residents by improving the natural environment. Unfortunately, each of their lives was cut short by acts of violence.

On the Anacostia River, the Earth Conservation Corps has had a substantial impact on the health and appearance of the Anacostia River, as well as on the people who work to improve it. The ECC is an AmeriCorps adjacent program that engages DC teens in environmental service projects, almost exclusively centered on rehabilitating the Anacostia River. The Anacostia River intersects with the Potomac River after branching through Prince George's County, Maryland and the eastern part of the District of Columbia. The ECC was technically founded in the late 1980s, but since 1994, it has inhabited an old restored pump house that juts out into the Anacostia River. The pump house is just south of the Navy Yard complex and almost in the shadow of the Frederick Douglass Memorial Bridge.

After making the pump house home in 1994, the ECC has seen tremendous change in the built environment around it over the next 25 years. Dozens of new residential and commercial buildings have risen around the pump house, including adjacent apartment and office buildings as well as the Nationals Park baseball stadium. All the while, hundreds of DC youth have worked on the river, learning about, cleaning, monitoring, and improving the Anacostia little by little. With the work of ECC teens alongside infrastructure and policy advances related to cleaning up the river, we’re at the point that development is now ongoing on both sides of the riverfront. This particular segment of the Anacostia River has become a residential, commercial, and green space destination for area residents.

Diamond Teague Park on the Anacostia River.

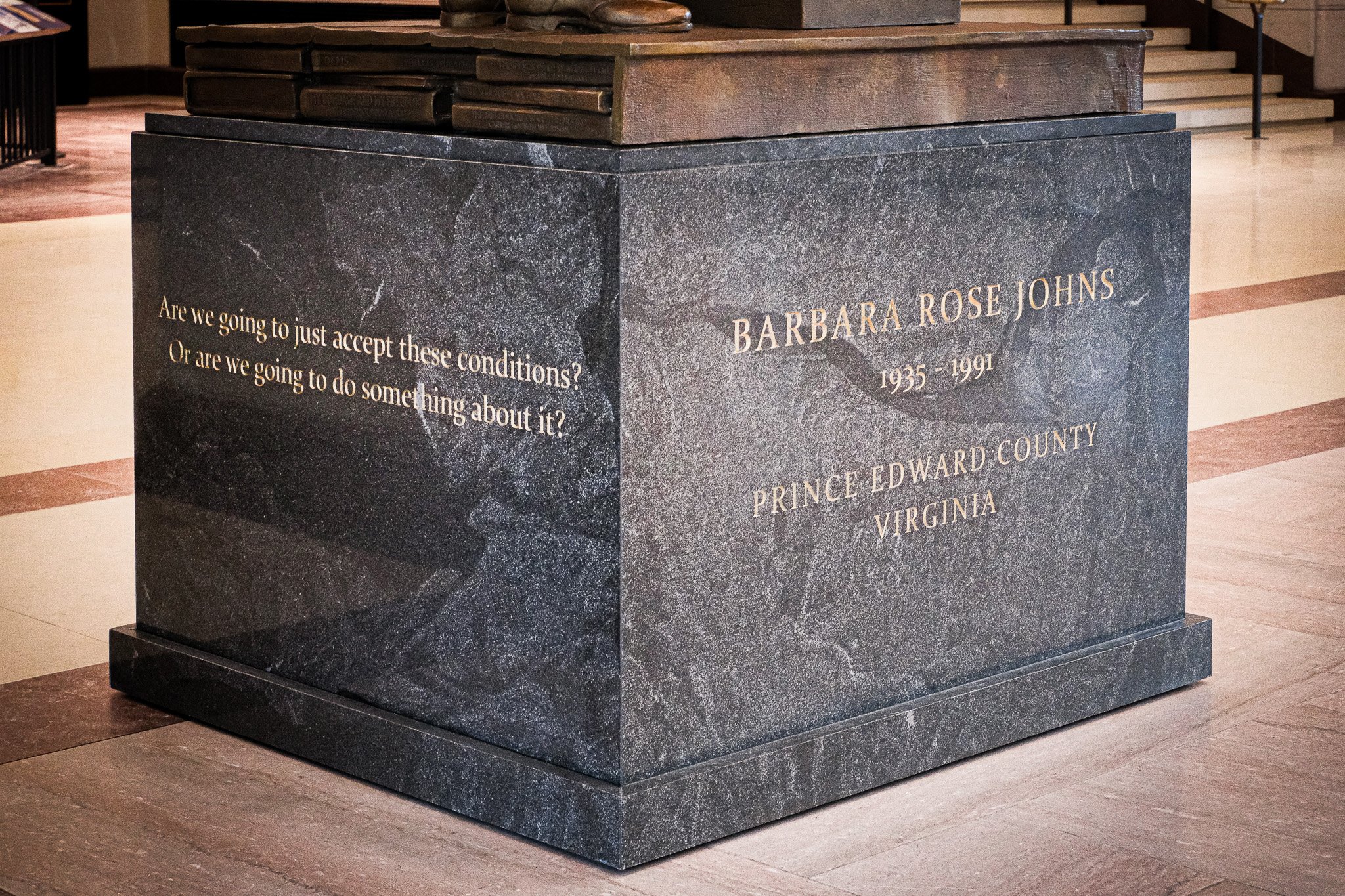

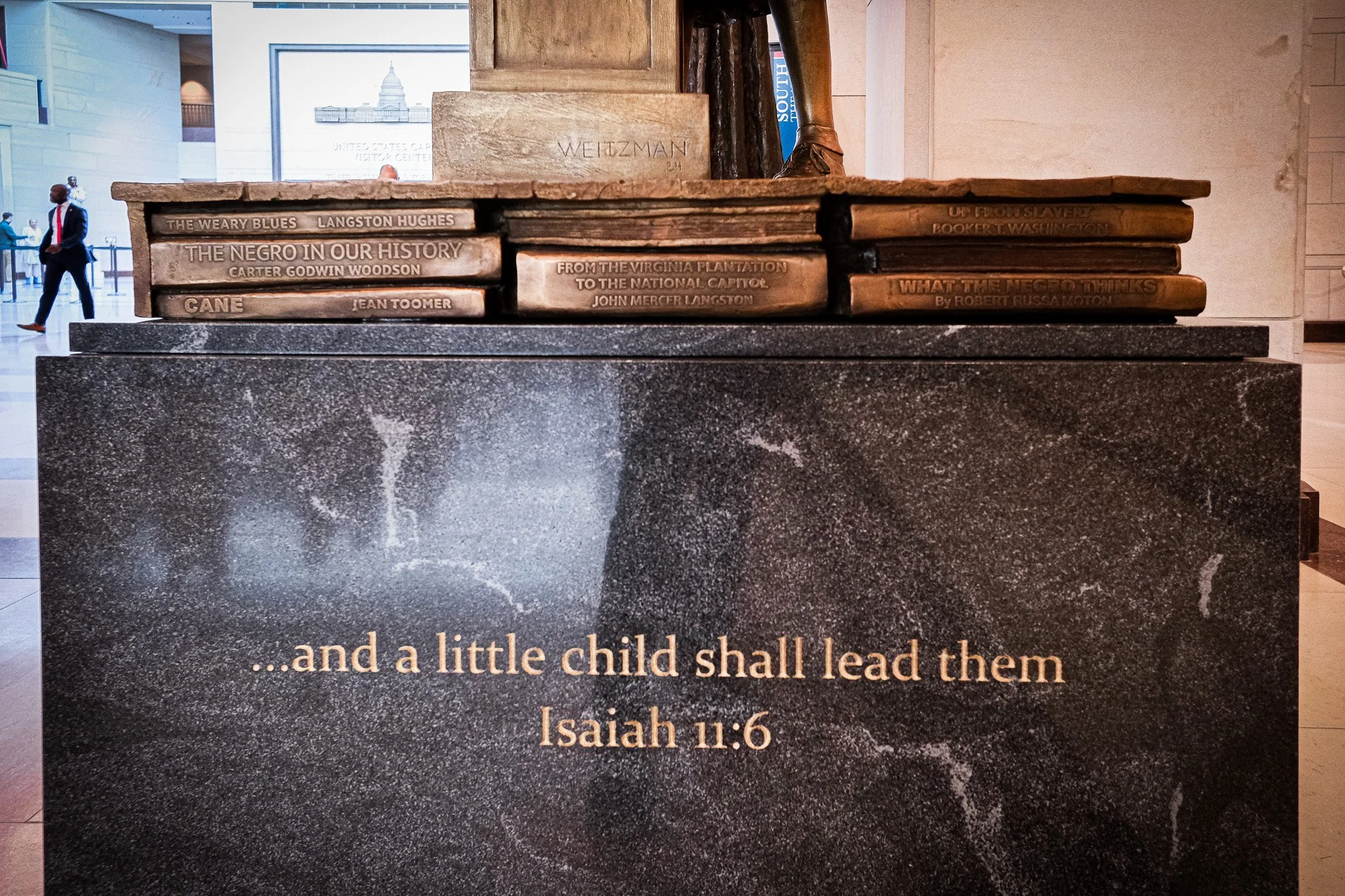

In between the ECC pump house learning center and the baseball stadium sits Diamond Teague Park. The park was dedicated in 2009 to honor Diamond Teague. Diamond was a teen who grew up in DC and worked in the ECC cleaning up the Anacostia River. Specifically, he worked a seven month program helping to bring the bald eagle, sturgeon fish, and the barn owl back to the river shed. In October 2003 a still unknown person shot Diamond on the front porch of his own home. Diamond died at age 19 years. He was known as one of the hardest working members in the corps and a friend to all. After graduation from the corps, Diamond was set to attend the University of the District of Columbia where he had just been accepted. He would have been attending with a scholarship achieved through his work on the Anacostia River during his ECC AmeriCorps service. Corp members and staff grieved after his death as Diamond's passing seemed to go unnoticed by the city and underreported by the media. It was the student media at the ECC who produced a video tribute shown at Diamond's memorial service. The day after the memorial service the mayor visited with Diamond's mother and ECC members.

Five years later, a Major League Baseball Park was built across from the ECC pump house, supercharging development around the area. Six years later, in 2009, then DC Mayor Adrian Fenty spoke at the groundbreaking of a new 1 acre park that was officially dedicated to Diamond Teague. Diamond Teague Park includes a new approach to the riverside and the ECC learning center, direct access to the river with a new boat landing, piers for water taxi and kayak access, and acts as a connector between two residential areas along the much improved Anacostia River. A river Diamond himself helped to rehabilitate. The park also incudes a tiled memorial sculpture to Diamond by artist G. Byron Peck, although it has fallen into some disrepair. The area around the park has seen incredible change over the past 15 years, but the commemoration for Diamond Teague remains. There are plans to enhance and enlarge the park with new features and landscaping, but that is tied to future real estate development on the waterfront. More recently, there has been a proposal to restore, preserve, and protect the memorial sculpture to Diamond specifically.

Diamond Teague memorial by artist G. Byron Peck.

Most tiles are missing from the top side.

At the end of Diamond Teague Park is the aforementioned, repurposed pump house. Now renovated and used for programming by the ECC, the pump house is named to honor Monique Johnson, one of the founding Earth Conservation Corps members here in DC. By 1992, Monique had transitioned into a leadership role as a young adult and was on an environmental rehab trip in Texas when a Houston man took killed her just days after her arrival. The Earth Conservation Corp group was there ostensibly to help clean up a local bayou, but primarily to be honored by then President Bush as participants in the Thousand Points of Light community service initiative. It was a celebration that did not happen. Monique was lost to us as she was exporting the challenging but important work on DC’s natural environment all the way to better another community in Texas. Yet, violence followed.

Two years later, the old pump house gained a new life as a learning center as well as a new name, the Monique Johnson River Center. Monique was one of the inspired young leaders who helped make that part of the river inhabitable for the Corps as well as all the development that continues through today. ECC members did eventually get to visit the White House in 1999 as invited by then President Clinton and Secretary of the Interior Bruce Babbitt.

Monique Johnson River Center.

Naming buildings and places after people is not new, of course. Place names can be purchased via sponsorship, or as an acknowledgment of philanthropy. We honor people foundational to institutions, or people who are widely admired. Sometimes it's a combination of reasons.

Diamond Teague and Monique Johnson were both foundational to advancing the mission of the ECC, but they also did so in this exact place within the District of Columbia, in service to the people — and flora & fauna— of the District of Columbia. These commemorations are multi-faceted; 1) to remember Diamond and Monique as people, 2) honor their contributions to the organization, and 3) through those contributions, honor their service to the community at large.

Over the past years, the Corps has lost many participants to violence. For anyone enjoying a walk on the rehabilitated riverfront or enjoyed looking over blue heron, turtles, and ducks on the river after a baseball game, much is owed to these teens, young adults, and their educators at ECC. The built and natural environments should not be separated from the human experiences of people who live amongst them. Being able to enjoy the river is important, but so is mitigating the violence that has interrupted so many lives in the city.

Hopefully people encountering Diamond Teague Park and Monique Johnson River Center take a moment to reflect on these commemorations, who the people behind the namesakes were, and how they helped make DC a better place.

Questions I still have:

What do you think about a public nature park as a form of commemoration? What about naming a building after someone?

How do we best honor work that is often unseen like cleaning parts of a creek many will never encounter or improving animal habitats deep into a forest?

How do we reconcile our want to honor the work of people like Diamond and Monique in such a public way only, but only after their deaths?

In what ways can we ensure the next generation are able to access and remain engaged in these types of commemorations?

Learn more:

Read more about the Earth Conservation Corps.

See videos from the dedication of Diamond Teague Park.

ECC Monique Johnson River Center.

2007 interview with a founder of the DC ECC.

2017 write up of the ECC.

Endangered Species, a 2004 documentary on early years of the ECC and the lives of its corps members. Moving, raw, and essential viewing for recent DC history.

Shoreline of Diamond Teague Park on the Anacostia River. The baseball stadium is not far away.

Diamond Teague Park.

Walkway down to floating pier next to the park.

Riverwalk boardwalk leading up to the park.

If you appreciate these examinations of commemoration across the DC memorial landscape, please consider supporting my work on Patreon. There we continue to look at the history, present, and future of commemoration in DC.